You Can't Hide Child Slavery with Skeuomorphism (But Apple's Sure Trying)

On moving towards an understanding of the designed interface as complicit in neocolonialism. And why I hate Liquid Glass.

While I was writing this essay, Apple released their new Liquid Glass design. This design, which is essentially a sleek, glass-like interface, is the latest in a series of updates from Apple that have left many unimpressed. It's a prime example of Apple's design strategy, minimalist, with just enough 'innovation' to warrant a new keynote, but not enough to truly stand out.

This kind of repetitiveness is why many designers and users alike now want more "fun" design. People don't want another minimalist interface that looks the same as all the other minimalist interfaces. People wish for tech to be fun again! Companies like Google and Airbnb are eagerly leading this trend to bring back a more 'enjoyable' internet experience, coming back to more gradients, more texture, and less flatness (Enjoyable for whom, exactly? We'll get to that.)

On the surface, this appears to be an improvement. Technology is shifting towards a more human-centred approach, moving away from the clinical minimalism to which we are accustomed. Designers and cultural critics alike lament the times when "the internet was fun" before corporations took over, with video essays abound discussing the topic, arguing that this would combat the corporate nature of the current internet. I've made a few such arguments myself, mainly because it's a more appealing way to get people demanding platform alternatives than explaining the ethical issues.

But this story about "fun design" is, at best, a limiting one. Stories are appealing. The overarching narrative slightly bends the facts and ignores those that are not relevant. Stories get clicks, stories sell books. Having a story that neatly explains all the problems with technology gets people's attention.

the supply chain issue

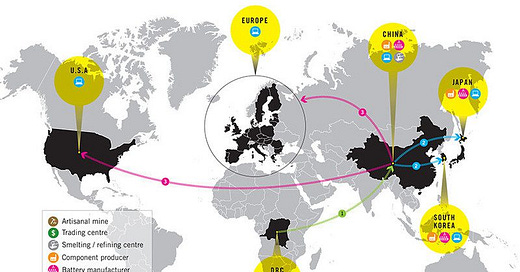

In December 2024, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) filed criminal complaints against Apple, alleging that the company had been 'using deceptive commercial practices to assure consumers that the tech giant's supply chains are clean.' This is all about 'conflict minerals' – a term used to describe minerals that are mined under conditions of armed conflict and human rights abuses. In essence, these are minerals dug up by people who are essentially enslaved. This case is being pursued in the EU due to its strict regulations on imports of certain minerals. Apple, as always, denies everything.

But why is this rarely in the news? And why do designers never talk about it?

It is so easy to detach the software from the hardware. We can have endless, deeply intellectual conversations about Apple's latest UI tweaks, or the 'questionable' ethics of data capture, without once mentioning the well-known supply chain issues. You know, the ones involving actual human beings. The two sides of the devices we use every day are generally viewed as separate - one does not concern the other.

As a student learning Interaction Design, I devoured mountains of case studies about the interfaces attached to the same devices that caused this devastation. I wanted to learn. I loved them. But that wasn't the whole story. The devices I studied were the same ones implicated in devastating human and ecological harm. But we spoke of them as if they were ethereal objects. Floating in the cloud, detached from the materials they came from. This didn't make sense to me, but I couldn't figure out how.

Very quickly, I got the impression that my political views and my shiny new design career were meant to be kept strictly separate (foreshadowing). For years, I was left with a sense of discomfort and confusion.

I knew who I was, but Lou, as a person and as a designer, were not two compatible individuals. There were never examinations of technology or interfaces that resonated with my lived experience and views. It was always an objective matter, centred on a worldview that seemed alien to me. A worldview that didn't account for ethics in any meaningful sense of the world. Ethics were "can a colourblind person read this", not "does this harm communities or does it make people's lives better?"

But not politics. Not power.

This not only caused me a great deal of personal distress as I attempted to fit a square peg into a round hole, but it also limited me as a designer. Every designer has their own flair, their unique style. My thing is an encyclopedic knowledge of how technology in all its forms interacts with people and communities to benefit the few, rather than the many. How this works on a systems level, how social theories coincide with this, and what this tells us about individual design choices and the mindsets they arise from. This is not what your thing is supposed to be. People often find it harsh, especially those who want to offer jobs. But very few people will tell you this straight, which is equally unhelpful.

So I continued to separate the two parts of myself, until I realised I couldn't anymore. I wasn't going to get anywhere without my flair. No designer will. So, to hell with that. Now I say what I think, write what I think, and my case studies are typically far longer than what is advised.

As a result, about a year into starting this educational initiative, I began to connect the dots on the particular software-hardware-children dying in cobalt mines dichotomy. This was due to a wonderful book that I read recently titled "Documents & The Design Imperative to Immutability."

the document, colonialism & the interface, neocolonialism

The book "Documents & The Design Imperative to Immutability" encourages an exploration of design history that is rarely considered - that of the bureaucratic document and the practices and techniques that legitimise the power of administration. It calls for an alternative path of inquiry that studies and experiments with ways to antagonise the bureaucratic imperative of states and corporations.

The document has a long, long history of legitimising borders, passports and deciding 'who owns what land' (spoiler: usually not the people who were there first). It does this through design. The kind of design that passes under our noses, the type of design that is rarely considered "design" in the modern sense of the word. It's all about the boring bits that create the boring documents. Within each and every one of these "boring" documents, there is a long and storied history of designed violence. Whether that takes the form of rental agreements, artificially created maps that benefit the powers that be, or property and land agreements that make no account for Indigenous ways of understanding land ownership.

So what does this teach us about interface design?

Just like we view the history of the documents through an imperative to publicity, we view the interface in the same way. The interface and its design are seen as separate from the ecological destruction wrought by the devices on which it relies. Just as the implementation of borders through designed documents enacts more traditionally recognised forms of colonialism, the interface does the same thing with the gathering of minerals such as cobalt, enacting neocolonialism.

The interface as it exists (particularly in most modern operating systems) is rooted in this history of using documentation to extend and legitimise destructive colonial activities. Whether those colonial activities are pushing indigenous people out of their land, or making children work in mines to create the materials for the latest iPhone. Design, in all its forms, allows us to ignore and legitimise this violence.

This is closely tied to the tendency to think of design as existing across time and space, a concept widely accepted in design circles. As if a prehistoric handprint is morally equivalent to an app designed to extract your data and exploit global labour? This 'timeless design' fantasy conveniently removes the idea that design is historically situated. So, modern UX design isn't thought of as connected to the broader impact of technology. Like, say, those exploitative supply chains.

How polished the interface looks on a visual level grants the corporation that produces it with artificially created authority. Vague and exploitative terms and conditions that allow the data economy to thrive. Weaponised minimalism creates within each user an affect of luxury. This affect of luxury legitimises the corporations. The emotions the interface creates in users and designers alike make it easier to ignore the exploitation required to develop the devices themselves.

facing the problem

It's a lot like Big Tobacco. People need to see the destruction caused by the thing in their hands. And carefully designed cigarette packages helped people deny this reality for decades. So, naturally, carefully designed interfaces are doing the same job for Big Tech. Out of sight, out of mind.

Given Airbnb's impressive track record of harming local communities, it should come as no surprise that the very same 'design visionary' who designed iOS 7 is behind their latest overhaul. Everyone is talking about it because they dared to use 3D icons (gasp!).

On a visual level, I am a huge fan. But on a political level? Not so much. (ps. The same guy is now working at OpenAI, which, while questionable in terms of data exploitation, will hopefully mean AI becomes less shit.)

Designers and users alike love shiny things. We are all a bit like magpies. Geeking out over how Airbnb has destroyed flat design in one fell swoop, while they are also destroying communities all over the world.

Being from Scotland, I am all too aware of this. Buying properties to rent out as holiday homes and squinting at us in disgust whenever we speak in a way they don't understand.

But look! They have 3D icons! Look at those 3D icons! So revolutionary! It almost makes you forget that they're actively gentrifying entire cities. Almost. Plus, he's just the design guy. What does he have to do with all this?

Imagine if the Airbnb website were legally required to include images of people who have lost their homes due to their antics. Of the signs in Barcelona telling tourists exactly what they think of them. Would you be so keen to book through them? Or would you look for an alternative? But when you can ignore this, because of the neat new icons, the destruction continues.

Fairbnb is an up-and-coming organisation that puts half of the profit from each sale into a local community initiative, and has strict rules about how many can be available in each area. So, why aren't they more popular? Well, doing good isn't as sexy as being a 'design god.' Part of this is because of the designer-as-identity paradigm. Because who needs ethics when you have a personal brand?

the myth of the hero designer

The use of sleek design to make us not question where our devices come from is deeply tied to the veneration of the designers of these interfaces. The Myth of the Hero Designer describes the tendency within design to valorise designers you admire, to think of them as the hero in the story of linear technological progress, where we are steadily marching towards a bright future. (A future, presumably, where no one asks about the supply chain.)

The interviews, the Ted Talks, the shiny coffee table books that we all collect like magpies collecting shiny coins - they all prop up this mythos that, in turn, props up and validates an industry that spends far too much time distancing itself from any moral responsibility. Because, you know, 'innovation' is a great excuse for everything.

Understanding this myth is key to dismantling the hold that Big Tech has over us, but it has become so normalised that this involves a lot of work. To realise how flawed this myth is, it can be useful to put yourself in the shoes of these "Hero Designers"

You've led a team that designed something revolutionary: a new OS, an interface that 'changes social media as we know it,' or some other world-altering pixel arrangement. This is never done alone. The features we think of as revolutionary - iOS 7 or a new design system for Airbnb - are not designed by one person. That would be impossible.

You get invited to an awards show, a TED talk, or a graduation at a prestigious design school. You're asked to give a speech. You go up to the stage and don't once mention the team of designers who helped you bring your vision to life. You don't mention the senior designer who had that brilliant idea that changed the course of the project. You don't thank the juniors and interns who stayed up all night creating endless mind-numbing variations of the single feature so that this wonderful idea could be carried out. You don't thank them. You don't even talk about them. All you talk about is yourself.

As someone who is endlessly optimistic about human nature, I'd like to believe most of us couldn't stomach talking about ourselves that much. It's certainly not standard in other fields. An actor who doesn't thank a laundry list of people who helped them is practically ostracised.

But in design? It's a prerequisite for 'thought leadership", whatever that means nowadays.

When I first encountered this argument in "What Design Can't Do," it completely changed the way I thought about myself as a designer. It made me reflect on how I brought my values into design—and how those values differed from those of the people I thought I admired.

I'm under no delusion that I have the design skill (or, frankly, the drive) to create something 'revolutionary' enough to find myself in that position. However, what I can do is contribute to a culture shift—a shift where the people who do make these decisions are made acutely aware of their role.

That's why each and every one of us, as designers and as users, has a responsibility to deconstruct this idea of the Myth of the Hero Designer, because we are the ones who make them heroes in the first place. And if we can, collectively, take that power away from them? Perhaps then we can address the state of extractive and exploitative technology. Maybe we can do something about the children dying in cobalt mines.

The "fun design" is the latest iteration of surface-level criticisms that isolate software design from the broader reality of technology, ignoring and contributing to the system that creates exploitation and ecological destruction with each new device.

The stories we hear about technology often focus on how individual gadgets or apps affect us personally, overlooking the broader implications. Not only do we forget about the children dying in cobalt mines, but we also forget about algorithmic control in the workplace, the digital divide, and the questionable usage of algorithms in the delivery of public services.

The consequences for Big Tech are no joke. Facing lawsuits or criminal complaints, as seen with the DRC’s case against Apple, can lead to fines, import bans, or stricter regulations. Loss of consumer confidence may result in decreased sales, investor backlash, and challenges in attracting talent. High-profile accountability can set precedents, pushing other tech companies to improve their own practices to avoid similar scrutiny. This accountability comes from making sure that people are able to connect the dots, making it easier for your average user to see past the sleek design. This begins with rethinking how we approach interface design and being transparent about the cognitive dissonance it enables, the same cognitive dissonance that perpetuates this destruction.

Reading List

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/01/child-labour-behind-smart-phone-and-electric-car-batteries/

https://fairbnb.coop/

https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/society-equity/congo-files-criminal-complaints-against-apple-europe-over-conflict-minerals-2024-12-17/

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/mar/08/airbnb-wild-disruptive-cheap-lettings-agency

https://www.setmargins.press/books/what-design-cant-do/

Great piece! Been exploring a lot of the same themes in our work.

There is a throughline of almost like "discipleship" (a faux spirituality) that permeates through design culture. We mimic it a lot in our language (objectivity and empathy are our only two guiding values almost taking the shape of metta in Buddhism). Design has never had any strong moral/ethical underpinnings, just feelings. Ives especially got at that through the Stripe fireside chat, talking about care yet not offering any tangible, actionable pathways forward for responsible design.

Design lands in some weird in-between space, borrowing from Objective Science Making and Deep Feeling that is almost Spirituality, but in the end, it is all turned towards something so nefarious.