we should all be designing tech like victorian scifi writers

on the joys of pre digital scifi, big tech scifi propaganda, the crisis of adaptation, an app that steals your memories (literally)

This is the final instalment (for now) in my sci-fi tech series. I wanted to finish on an optimistic note, discussing alternative futures, my favourite sci-fi authors, and fighting against the age of terrible adaptations of classic novels.

As I’ve explored throughout this series, the 2010s/20s saw a renaissance of classic sci-fi being adapted for screens, due to an increase in VFX technology and talent that allowed these tales to come to life for the first time. But this adaptation kick is not without its flaws. The construction of sci-fi worlds, in particular their technology, is widely understood in literature theory circles to be a world-building process that is part and parcel of the author's everyday life.

Sci-fi tales are constructed around a complex relationship with the empirical world, where what can be described as “fragments of cognition” allow a simultaneous distancing and closeness to the material world. In adaptation, however, it is hard to replicate these intentions, often contributing to the flattening of the moral or political intentions of the original authors.

Often, these adaptations are flattened by the technological and social norms of the time. The 1990 film Total Recall, inspired by Philip K Dicks 1966 novella We Can Remember It For You Wholesale, shows this in a very stark way. In the text, Philip K. Dick portrays a society where control is exerted through the ability to tele-transmit people’s thoughts, with surveillance reaching an extreme level. He does not describe how this is achieved - only that it is. In the 1990 adaptation, however, the technological imaginaries of the time dictated that this must be explained through the “computer chips in your brain” idea.

A particular aspect of the philosophical adaptation is lost in the original book. Once the ideas of these technologies become technically feasible, it makes it harder to make an abstract point about the trajectory of society, and it becomes more Silicon Valley porn than philosophical exploration.

There exists a tension between these two methodologies - the pre-digital sci-fi technology as constructed through the author's imagination, and the “bringing to life” of this technology in modern adaptations. When examining the increasingly important relationship between our digital age and the sci-fi tales that inspire (or predict) it, and the role that ideology plays in this, this tension can tell us a lot about what technology is, how it got here and, crucially, what it could be.

the masculinisation of sci-fi and the death of nuance

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) is widely considered the first work of modern science fiction, due to the way it draws on scientific and philosophical ideas as the foundation for speculative storytelling. From the 1920s to the 1960s, however, commercial science fiction became closely linked with pulp magazines marketed to adolescent boys, and masculine themes (space conquest, heroics, technophilia) dominated the mainstream. Female perspectives were marginalised, and women often had to write under gender-neutral or masculine pen names to be published.

The late 1960s and 1970s saw an influx of women writers (e.g., Ursula K. Le Guin, Joanna Russ, Octavia E. Butler) who explicitly explored gender, identity, and feminist ideas, subverting the previously masculinised norms of the field.

Capitalism needs specific narratives about progress, conquest, and individual heroism that justify expansion and exploitation. The pulp magazines, and the TV shows and movies that came from them, sold fantasies of technological dominance that perfectly aligned with the imperial projects of the 20th century, whereas the more thoughtful tales (often written by women) did not sell these fantasies.

Ursula K. Le Guin is THE BEST EVER (shant expand on that.) Her tales tell us about gender, colonialism, and the nature of time in a way that most science fiction tales could not even imagine doing. Here, you can see how this complex relationship between the empirical world and fragmented cognition gives rise to creativity, without the burden of trying to make technology make sense, as we often see in adaptations in the digital age.

The vast majority of her work hasn't been adapted into film or TV, making it hard to predict what the interfaces might look like.

In her books, it's clear that the focus is on the social determinants of technology. But in my experience of her work, what she doesn't say tells us just as much as what she does say. This is also interesting from a design perspective. There is a lot of buzz in all sorts of circles about "future interfaces"—what interfaces could look like beyond a screen. Much of the current research into this space is focused on wearable technology and smart devices. I find this to be quite dull.

Much like Asimov’s Foundation, a lot of Ursula K. Le Guin's work shows us a different world because she was not trapped by the perspective of technology equating to screens and buttons, and could think of technology in a broader sense. She once described technology as "the active human interface with the material world," whether that be tool-making or social structures - not just high-tech interfaces. This reflects a profound understanding of the nature of technology and its sociotechnical complexities, a perspective which is sorely needed in the age of Palantir and the AI Cult.

So, we ended up with a cultural consciousness rooted mostly in reductive, masculinised ideas of what technology is and should be, justifying and enabling the current state of affairs in the increasingly fucked up relationship I've been exploring this whole series, where tech capital isn't only taking inspiration from reductive masculine science fiction (Palantir, etc), but they are also funding it as a form of propaganda project. They know how powerful our stories are, so they are trying to control them by pumping money into tales that create the cultural consciousness that lines their pockets.

the apple tv+ industrial complex & enshittification of the imagination.

(NB: This headline is ironic, I hate the overuse of the phrase industrial complex, please stop it, it is annoying.)

The Steve Jobs hero’s journey, the minimalism and elegance. The cultural mythos surrounding Apple is what sells their products. The sci-fi shows funded by Apple through Apple TV+ feed into this ecosystem, creating propaganda that furthers the mission of Big Tech and platform capitalism. Apple TV+ is not even profitable, losing over $1 billion per year.

Apple's entire pitch with TV+ is to do something different: focus on prestige, award-winning, high-quality shows instead of amassing a giant, undifferentiated catalogue. So, everything on Apple TV+ is filtered through these values: sleek, optimistic, innovation-worshipping, always pitched toward a certain kind of aspirational future. Through this process, the original authors intents are usually brutally flattened.

Calling this a conspiracy misses the point. The real risk is that propaganda can happen as a byproduct of organisational culture, not just secret agendas. Apple doesn't need to consciously propagandise when their entire business model depends on selling us futures that serve their interests. Overstating intent only obscures the actual capitalist mechanism, which is baked into how sci-fi adaptation, funding, and corporate storytelling work in practice.

Stories inspire all that we create. When most of those stories are filtered through the values of the Big Tech companies funding them, it creates an enshittification of the technological imagination. Similar to the enshittification of actual devices, our ability to imagine the future becomes more and more filtered over time, becoming flattened and less diverse in its goals.

we don’t want a self driving car we want a moveable tapestry

The trajectory we see the "HCI of the future" going is entirely confined to smart devices, AI powered technology, and wearables—all holding potential, but none particularly imaginative. There's already significant negative reaction towards these technologies, but this is largely ignored under the assumption that resistance will quell over time, following a typical cycle where we slowly become used to our technological overlords. But this might not be the case. Research suggests adoption of wearables, AI and smart devices isn't following the typical technology adoption cycle. Rather than simply being "slow to adapt," many users actively disengage or resist, and these reactions are persisting well beyond the usual adoption lag.

This signals that we’re not watching a routine adjustment phase, but a deeper, more collective refusal. The HCI of the future will keep following this trend, with further slowing adoption and more hatred of data tracking. If technology continues on that path - which it appears to be doing - it won’t succeed. True HCI innovation now has to start with organised resistance, and the of building alternatives.

the mnemeion app: memory as contested terrain

This is exactly what the work “Towards the Realm of Materiality” sets out to achieve. This volume documents the exploration of alternative designs for some of the non existing technologies as described in Philip K Dick’s work.

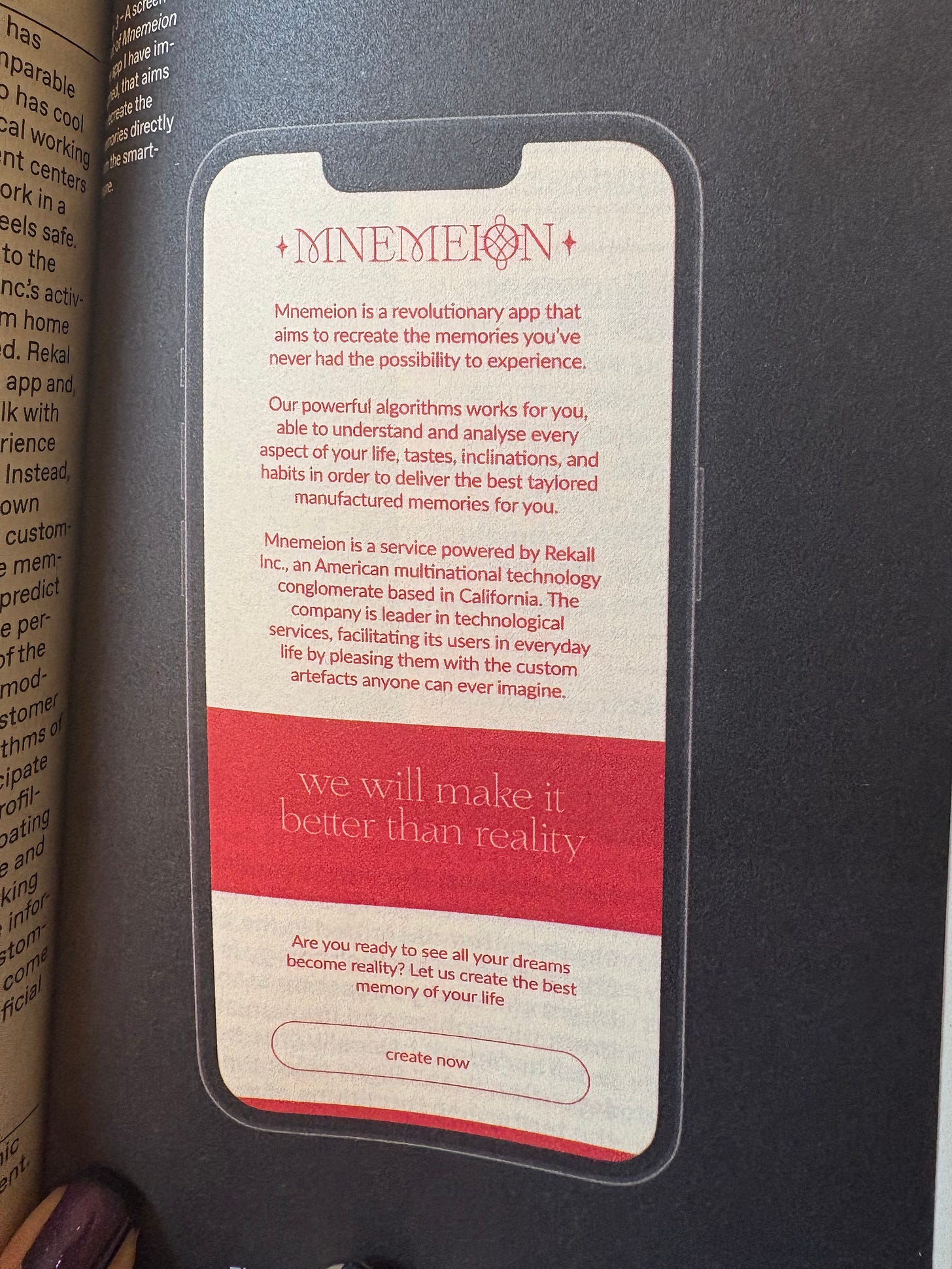

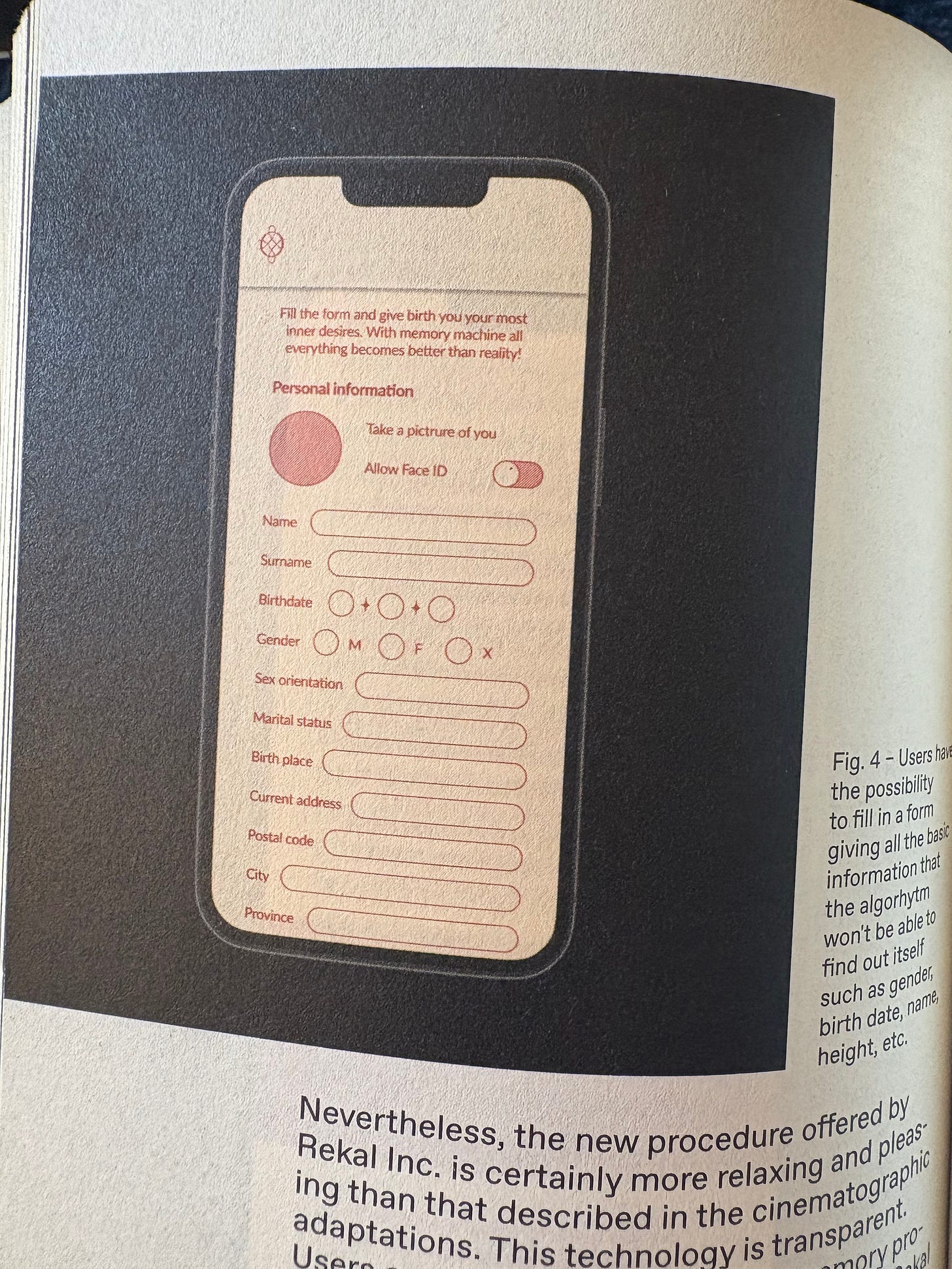

One of the projects that I cannot excavate from my mind is the Mnemeion App. This is a design fiction project which draws from explorations of memory as explored in 1966 novella We Can Remember It for You. It imagines an app that “implants memories” through a materilaised data collection process which “collects memories” using computerised mechanisms drawing from how memories and self-identity intersect with each other.

Where Dick allowed the means of memory alteration to remain abstract, the app is a design fiction that materialises these anxieties as a tangible, near-future interface. The eerie similarity of it to our own apps (particularly the “Allow Face ID” button. The accomanying essay describes how propoganda mechanisms similar to those of Big Tech - carefully designed “perks” keep the workers behind this mechanism going.

Through this, the project highlights an analysis of class and power that echoes the message I have been reiterating throughout this scifi series. In a more material, potent way through the literal control of memories being tied to capital - it's about who gets to control the stories we tell ourselves about our own lives.

The design processes described in the book draw on speculative design, but mitigate its well-documented innieficency through “speculative realism,” a design practise that uses elements of speculative design to create narrative technologies similar to that of sci-fi novels, focusing on the present rather than the distant future, blending the narrative tools of scifi and speculative design to ask better questions about what the future (or, the alternative present) could look like.

Using this modernised, blended approach achieves a dual purpose: using the best of scifi to reform our narratives around technology and sieze them back from propaganda projects funded by Big Tech, whilst also opening alternative avenues that show us a different way of living.

Philip K Dick’s work often examines the ability of objects to become concious, symbolic of his beliefs around consumer society, extraction and humanity where the objects themselves often rebel, showing the unsustainability of an extractive consumer society. This perspective makes it the perfect avenue through which to explore how this blended approach can tell us about our technological dillemas, as it explores how these objects exist within their ideological frameworks, how this shapes them, and what they may think about this if they could think as a reflection of the collective unconcious and it’s real beliefs about technology, underneath all the flattened propoganda.

The way the scifi authors of old were inspired - how their daily lives, their fragments of reality - inspired the wonderous technology they wrote about and the principles this technology stood on is exactly where we need to look to inspire the next wave of innovation. Not the flattened, capitalised, Apple-ified tales that are inspiring Silicon Valley technology. We can win the future - by showing people alternatives rooted in imagination, resistance and radical autonomy.

The masculinization of sci-fi feels tied to rationalist traditions and the objectivist ontology driving much of the AI project, past and present - knowledge comes from reason and logical deduction, rather than lived, embodied experience.

One of the things that is striking to me about Le Guin's work/the women writers of the '60s-'70s is how they align with phenomenology and constructivism - knowledge is situated in context. To your point, the active disengagement we’re seeing feels like a signal that people are hungry for a shift towards this situated approach.

You are correct LeGuin is the best. This whole series has made me have more discussion of sci-fi with friends and family hopefully not TOO annoyingly.