the children yearn for buttons, we should listen to them

a ux design-focused investigation of techno-nostalgia in it’s latest form: the yearn for the buttons and the yearn for the days of social media past, and how it can be used to advance a better future

Disclaimer: I am what you might call a Christmas Person (i.e. I am a communist unless it is December). Last weekend, I ventured to Edinburgh to go to the Christmas Market and buy things I didn’t need. As such, my brain is infected with The Christmas Mood. When I am like this, 60% of the metaphors I use are festive-related, and I feel like I am going a little crazy. My day job is in hospitality marketing, which has only worsened this year. As such, I would ask that you please excuse the excessive references to A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. And the amount of time it has taken me to write this essay.

So, we all want to return to the Ye Olde Internet—or at least a lot of people in my corner of the internet wish to. I understand this desire, and I have spoken about it before. Today, I would like to present an alternative proposal. I think this desire for the ghost of the Internet past can be harnessed to create a better digital future—but only if we listen to it correctly.

Platform Realism, as coined in the book “Stuck on the Platform” by Geert Lovnik, describes how many people today struggle to imagine the internet without platforms. Platform capitalism, he argues, has taken over our lives, and we struggle to imagine an age of decentralised networks. The small number of us who do, he claims, pose serious problems in making platform alternatives appealing to many users in the digital age.

I’ve spoken before about the problems of a return to decentralised platforms without much critical thought. I take two main issues with this:

In a neoliberal age, the decentralised internet always gave way to corporate hegemony. Many leftist theorists were warning about this at the time, such as the authors of “Resisting the Virtual Life” (1996) and “Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy.”. Leftists had a responsibility to heed these warnings and do their best to prevent these outcomes - and still do. Simply building platform alternatives did not work then and won’t work this time. The question of appeal is part of this, but so are other issues, such as funding, internalised neoliberalism, etc.

Accessibility. I was born in 2001, so I was not an avid user of platform alternatives back in the day, what with being a toddler and all. But I can’t imagine they were friendly for screen reader users or, from what I have seen, most definitely not people who are colour-blind. Then, there are issues with touch targets for users with motor issues, and the list goes on. The reality is that homemade platform alternatives built in your shed aren’t going to be inclusive of disabled users - because the people making them are likely unqualified in this department. Most professionally trained designers & developers struggle with accessibility, even in large teams. How are two idiots building a platform alternative in their shed meant to account for the diverse needs of disabled users? They aren’t.

This essay will explore why people long for the internet of the past and what these feelings reveal about our desires for technology in a post-capitalist future. While I've previously discussed the dangers of uncritical techno-nostalgia, I believe this collective yearning represents legitimate frustrations with our current digital landscape. We might harness these desires with thoughtful UX design and critical analysis to create meaningful alternatives to platform capitalism.

the buttons thing

But lately, something has begun to emerge from the darkness—a potential pointer towards what we could do to make these platform alternatives appealing. It's the buttons thing. If you are on the same side of the internet as I am, you will know exactly what I mean by the buttons thing.

Across the internet, there have been calls for the return to the age of buttons. Buttons are fun. Everyone likes buttons. Touchscreens are boring; no one likes them anymore. Part of the root of this call for the return of buttons is the idea of embodied cognition and the rejection of the computational theory of mind. Embodied cognition is the reminder we all need that we exist in the world with our whole bodies - so our experiences with technology should account for this. Alternatively, the computational theory of mind advocates that our brains are simple input-output machines (this is nonsense, but it is everywhere in technology & design).

Buttons present tactility - we like to touch things. Touching things is fun. This is where I return to the idea of whimsy - rejecting conventional technology in favour of a better digital future has to involve rejecting the ideas that traditional design of technology supports. Due to the ever-present computational theory of mind, over-rationality spurs technological development, justifying and creating the ideas behind the data-thieving algorithms and the persuasive design techniques that enable them. So, to escape this, we have to return to fun. Whimsy. I’ve written about this before in more depth in my essay about Letterboxd.

However, at a deeper level, I wonder if we are chasing ourselves in circles. I remember when touchscreens weren’t everywhere when they were a novelty. I would have been between the ages of 4 and 8. Whenever we would go on a family trip to the shopping centre nearest our city, my cousin and I would race each other to the map. Why? Because it was a touchscreen, and we rarely saw those. It was a novelty. Is what we are seeking in buttons simply a novelty? Or is it a signification of a more profound desire for change at the structural level of technology?

I would argue that it is both - we want novelty and fun. We want whimsy, as I’ve spoken about before about letterboxd. But, we also wish for more profound change - because whimsy without principles behind it is still capitalism, unfortunately. Whimsy can be a powerful tool for change - but only if it stays whimsical. When Big Tech begins to take and over-analyse it, it becomes less whimsy. Then we want a different whimsy - the real whimsy. This is the cycle of techno-nostalgia. We can only escape it when there is more than just surface-level change.

But - this desire for buttons & novelty does provide a gateway into this structural change. People will use a platform alternative if it is fun and silly, and then they are exposed to different ways of being on the internet. This can be in the UI, or it can be like a curation algorithm, or it can be in the quality of content, or it can be a little more complicated to grasp than that. It can be in the structure of the platform alternative and how it represents how humans interact with one another, the world, and the internet - the structure should describe rather than prescribe.

it’s not about the buttons, really

What people are expressing when they express a desire for buttons is a desire for change - the design of technology reflects its internal workings. Most humans, at some level, understand this. The difficulty is pointing a finger at the real problem when you’re not sure how it all works in the first place. So, this is where design education comes in.

Today, social media interfaces are sleek and captivating. Likened to a slot machine, they can draw us in, and then the algorithms behind them steal and sell our data. What we see when we see the touchscreen interfaces is a carefully crafted lie, so that we don’t question (too much) how the technology works. Most people who spend enough time online have an intrinsic understanding of this.

Buttons, then, are seen as a way to escape from this - because we can touch buttons with our fingers, they feel more real. We know what a button does. At least - that’s the idea. Unfortunately, as the bastions of the early democratic internet learned the hard way - no matter your intentions, something can and will be taken over by corporate interests. We are already seeing tech companies clamouring to make the most out of the buttons thing.

Before people figure out what their real problem is, pacify them! Sell them some buttons! Then, in 5-10 years, they will use those same buttons to mourn the age before buttons, the good old days. Whether it's buttons, social media platforms, blockchain, or Web3, the list continues—it’s always the same.

Ultimately, what this cycle of techno-nostalgia shows us is 2 things:

People want the design of their technology to reflect its inner workings

People want these inner workings not to be outright evil

People want a little bit of silly

This isn’t that difficult. But until technological literacy is widespread enough that people grasp this and can effect change, we are going to be stuck in this cycle. Ultimately, a lack of education prevents us from getting out of this cycle (cough, cough, subscribe to my substack, cough). People aren’t able to recognise what they don’t understand.

algorithmic transparency through design that is fun

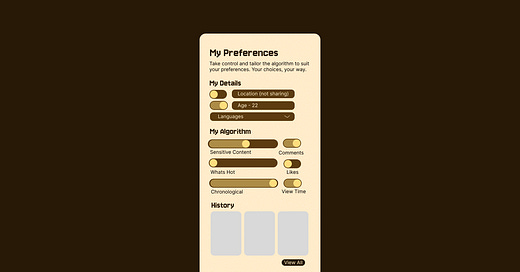

So - if people want technology to reflect its inner workings so they can better understand the logic behind the tools they use every day, what does that look like? Something like this, I would imagine. I mocked this up quickly to illustrate what I mean - if people are interested, I can develop this prototype. I aim for a feeling of “tinkering” with your social media feed, as a character in Star Trek may fiddle with buttons. This is intended to give the users a sense of autonomy.

industrial + digital

In an age where people don’t just want to rethink their interfaces but also their whole experience of digital tools, we will also have to rethink the devices themselves. As I mentioned earlier, a core part of my design process is tackling assumptions. In this case, I have assumed that the solution to this can be presented through a digital interface on a modern smartphone - but what if this isn’t the case?

But I’m a UX/UI Designer—not an industrial designer. So, I haven’t the faintest clue what a rethink of our experience of devices themselves would look like. Exploitative ethical technology will require cooperation because I can only work within the constraints of the devices that exist.

So, if you’re an industrial designer who’s read this and has any funky suggestions about new devices, please let me know!

Recently, I have become interested in the role of blue light. Blue light, as I’m sure you’ll all know, is what makes our screens “light up.” But smart devices don’t have to have blue-light-based screens—Kindle Paperwhites are a great example of an alternative option.

My approach to technology involves a strong belief that digital technology should not be viewed as “not real” or somehow different from analogue technology or other non-digital artefacts. The digital should be a part of our environment—a part of our lives. This relationship may be complicated to reform when it is so aggressively different through its screen.

technosolutionism, rationality & class consciousness

Nostalgia can be more than mere escapism—it can be a powerful tool for imagining alternative futures. When we examine techno-nostalgia critically, we find it represents a longing for simpler technology and a more profound critique of our current digital landscape. While social media often amplifies and spreads this nostalgic sentiment, it also provides a valuable window into collective desires for different ways of engaging with technology.

To design a better digital future, we need to be better people. Being better people makes us better designers. Design culture suffers from egotism meant to protect us from our capitalist fate. Neoliberalism teaches us to care only about ourselves and our place in the social hierarchy - and designers often swallow it right up.

Designers and technology professionals often ridicule those who long for the Internet of old. This reaction is embedded in the cultures of technoptimism and techno-solutionism that exist in the tech industry.

Technosolutionism is the idea that most problems can be solved with technology. It describes our society's tendency to present a more technical solution when a simpler one would work better.

Technooptimism, as coined by He Who Shall Not Be Named (Google it), is the idea that technological development always benefits society.

Both of these preconceptions are often unconscious. This is a plague on our society, and bad design is, too. Good designers are curious and question their assumptions about the world. Instead, what often happens when design decisions are made regarding the

When someone makes a video expressing their desire for a physical button, someone else who has rested their identity on being someone who designs touchscreens may feel attacked - then the discourse descends into chaos, and no productive solutions are reached. This happens when designers rest their identity in being “a designer” - when it becomes a central part of who you are. That is often what leads to bad design - you are designing for other designers rather than the people using your designs.

This leads to a greater and greater disconnect between the technology we use every day and what we really want from technology. It works because it is intoxicating. When pressure is applied to constantly increase engagement metrics, designs become worse and worse. This is a form of enshittification.

Those who create and critique technology should never consider themselves superior to technology consumers or the dreaded technophobe. This mindset is just another manifestation of capitalist thinking that we must overcome. Instead of dismissing nostalgia for older technology, we should embrace curiosity. Co-design practices - where users actively participate alongside designers - are a key part of the design process. This approach, combined with bottom-up technology development (where solutions emerge from community needs rather than being imposed from above), could help create digital spaces that better serve people's actual needs and desires.

The key question becomes: Instead of assuming we know what people want from technology, why not engage in meaningful dialogue with users and build solutions together? This means seriously engaging with what people actually want when they express nostalgia for past technology, not just dismissing them as fools.

Recommended Reading

https://valiz.nl/en/publications/stuck-on-the-platform

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/31873/summary

https://archive.org/details/resistingvirtual0000unse

My only qualm with your article is that I do not want a little bit of silly. I want a LOT of silly!!! 😤

I loved buttons!!! i resisted giving them up for yearssss. I was a late adopter of the touch screen and very vocal about how stupid I thought they were (as I type this now on my iPhone 😩)