make local tech weird again

why local tech thrives in some communities, and not others. on scotland, language, cultural consciousness, and the legacy of bureaucracy

EDIT: I have such beef with Substacks schedule feature, it keeps deleting things out my posts. This is the WHOLE essay. Do ignore the first email!

Recently I attended one of the Relational Tech Project’s show-and-tell sessions. The first presenter was showing us her built-out service for a local lending library, which has been a resounding success in her local area. This project started from her avid interest in local facebook buy-nothing groups, which she wanted to take away from a dependency on Big Tech.

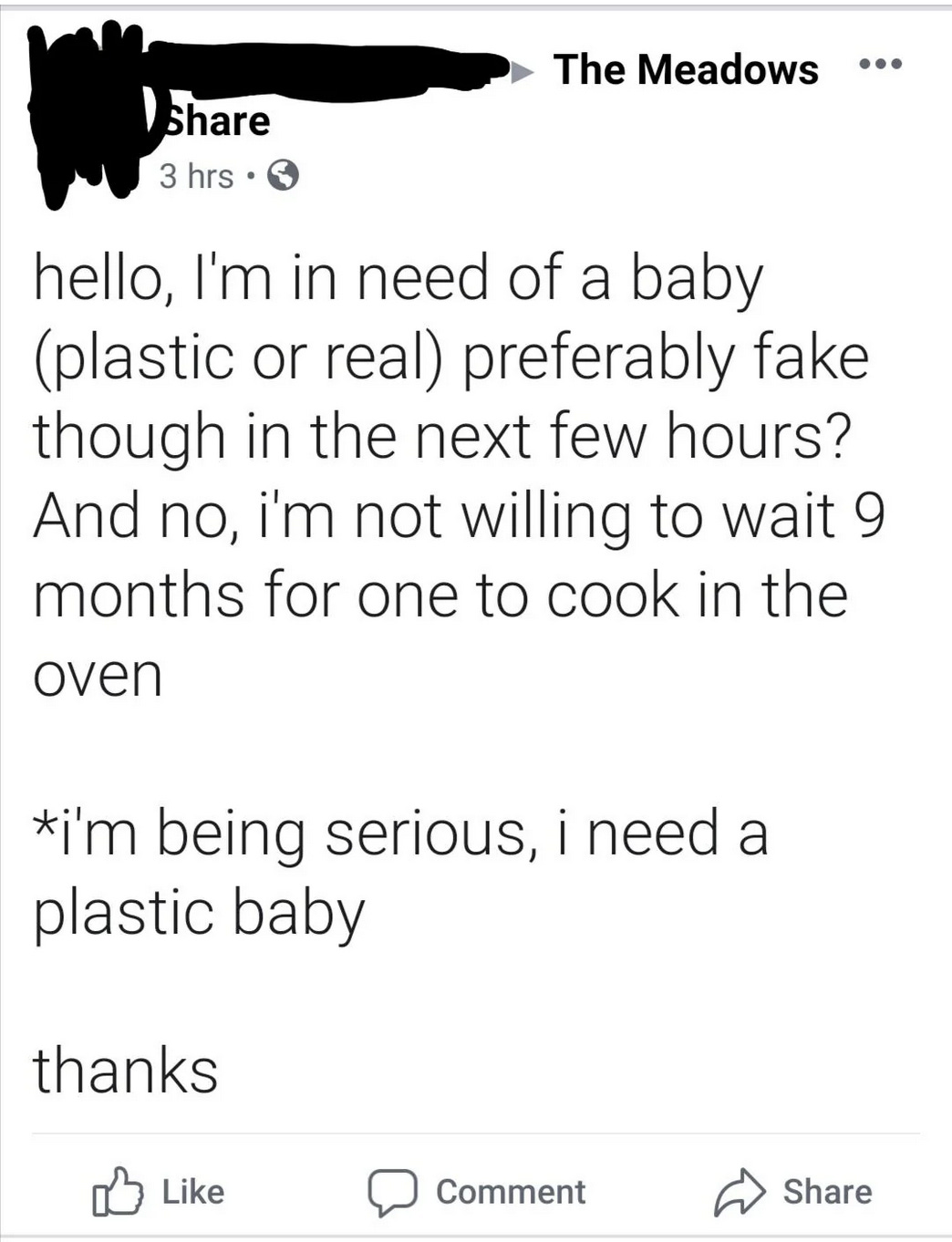

Listening to her presentation gave me rather visceral flashbacks to 2019, Edinburgh, when I was a fresher and had just discovered the ups and downs of the infamous Medowshare Facebook group.

This local legend led to more than a few debacles that involved myself and a band of fellow freshly-18 year olds tasting free will for the first time cavorting down the Pleasance with houseplants we had received for free at 3am (I was the only sober person in this group, and they were very large houseplants). A seemingly wise third-year had told us that if you saw something good on Medowshare, you had to get it quick. So get it quick we did.

Anyone who has spent any amount of time in Edinburgh will likely have a similar story. Lifelong friends (and mortal enemies) are made on Medowshare. If you are ambitious enough, you can furnish an entire student flat through Medowshare (although I would not recommend it unless you want a nasty case of mould). And a word to the wise - do not attempt any Medowshare related escapades during the month of August.

This was one glimmer of hope for me — the one experience I could think of that showed me what local technologies could be. But it was only one in a sea of many that I, and those around me, never really connected with. This essay is an exploration of why that is, specifically in a Scottish context.

linguistic suppression through technology

When I first started primary school, I distinctly remember several comments being made about the way I spoke. I was raised in the West End, but between my parents, grandparents, and my temper - I didn’t sound like I was. This didn’t go down well, so I quickly started copying the other children in my class.

It wasn’t till 15 year later that I started to reflect on this, after having to bring my less-than-West End accident out of the scary cupboard in the back of my subconscious in order to scare off some creepy men in clubs. After a few of these incidents, I became aware that I felt more like myself when I binned the West End accent. This feeling was likely due to the fact that despite modelling myself to fit the Tarquins around me, my inner monologue never really changed, so this person and the person that comes out of my mouth are two drastically different people.

This was where my interest in the promotion of Scots language initiatives began - it was how I first learned that it was a language in the first place. Unfortunately my West-End accent is mostly rooted in anxiety - which I am plagued with, and cannot get rid of, so it is here to stay unless you have the unfortunate pleasure of getting to know me better. But the interest remains, which is how I came across the Scots translation of the Firefox browser.

This discovery was a culmination of my personal reflections and my growing passion for technology design, so I dove into it headfirst. During the course of this discovery, I got in touch with the lovely people who translated the browser in the first place - I was deeply interested in the design question of adapting a language to the digital sphere, where that has not been done before, especially in a language which, like most minority languages, is not widely standardised.

It has been to my displeasure that this service is not widely used - most people I tell of it don’t even know it exists. The Firefox browser in Scots has the potential to become a powerful local technology, but it isn’t there yet. You could attribute this to the lack of interest on the part of the powers that be in Scotland in really investing in the advancement of Scots, despite the fact it has significantly more speakers than Gaelic (if you were bold, you could attribute this lack of interest to deeply rooted classism).

Most Scots speakers use the language interspersed with English, and many argue this means it is more of a dialect. But this is a chicken or egg situation. How are speakers meant to advance their use of the language without investment in the language? A minority language being used interspersed with the dominant one is a very common characteristic in linguistic development across the world - the treatment of Scots as an outlier to this is nothing more than ignorant confirmation of centuries old biases against Scots speakers. This usage of the language is an argument for investment, not an argument against it.

Educational programs that show people what modern Scots writing looks like. Road signs in Scots. News programs. Advance the language so people can use it - all most speakers need is a bit of encouragement and validation. Validation that it isn’t slang, it isn’t lesser - and they should not be punished by self-important English teachers on their usage of the language (that one was aimed).

local technologies come from local history

The reality of local technology is that it is deeply tied to local histories - and how those local histories have been ignored. How local can local technology be if the words it uses, the button labels, the descriptions, the arrogant voice assistant - are all written in a language that most of the local people only use when they are required to in an academic or professional setting? Not very.

Local technology should speak the way people speak - or it is not local technology at all. Introducing a local technology in “Proper English” into Scots speaking communities will always give it the impression of yet something else that is imposed on them by well meaning, yet extraordinarily condescending, English people, Americans, or worse, West-Enders.

what even is technology?

It is all too easy to feel yourself unable to imagine what local technologies are, and what they may do to serve your communities, if technologies introduced to your community have rarely served “local” purposes. In this case, I mean technology in a more broad way than we usually think of it - “the active human interface with the material world.” - which encompasses all tools and methods for survival and daily life, like a knife or a piece of paper.

These things too are technologies - computers are one technology in a long line. While it may be popular to think of them as somehow categorically “different” from anything that came before, they are merely more complex. A communities history with past forms of technologies impacts their view of current technologies. When thinking about local technologies in the modern sense - Facebook buy nothing groups, browsers in local languages - as part of a resistance to Big Tech, we have to remember that this is part of a history of technology being controlled by a dominant elite, not a separate phenomenon.

And that is why analysing the history of bureaucracy is important in understanding the landscape of local technologies. Bureaucracy itself is something we often take for granted - but it’s not always been that way. During the late sixties and early seventies, there was much debate about what it was, how it should be used, and how it related to the world around us. Since then, we’ve all became used to it.

In Scotland, these outcries looked a little different than they did in other areas. By most assessments, Scotland did not experience the “swinging sixties” and it’s rampant critique of bureaucracy in the way it is typically thought of. Society was changing under the surface, with the SNP starting to shift and begin their slow rise to power alongside the steady decrease of rampant sectarianism. These shifts deeply affected modern Scotland, and her relationship to bureaucracy.

Alienation and control enforced by state welfare bureaucracies and centralised governance were felt throughout the fabric of Scotland during this time, and in all the time since. So, when everyone starts using fancy new American smartphones — this awakens that same cultural memory.

A cultural memory of Anglicised bureaucracy, a Scotland facing cultural changes that went largely misunderstood and sidelined, a Scotland that struggled to find her voice. It’s easy to expect ourselves and our communities to fit into the majority perspective of what political change looks like, what local technology looks like.

But in a country with a sh*tstorm of linguistic oppression (and it’s resulting emotional closed-off-ness), stereotypes that paint us as grumpy when we are really angry, and rampant racism and white supremacy all co-existing at the same time? That local technology won’t just appear. Just like political change, it must go hand in hand with a level of collective reflection, deconstruction, and rebuild.

the design zietgiest

It can be easy to construct an idea of local technology as a designer, disconnected from your local-ness. Design is often sold to us as some separate, untouchable entity away from our lived histories. Throughout my time learning design, I never felt there was any space for the person I was at my core, because of my histories.

I always found this isolating, but after I graduated I happened across a copy of What Design Can’t Do by Silvio Lorusso. This book outlines the collective design conciousness, putting language to that exact disconnect I had been feeling for years. Platitudes about the “power of design” are everywhere, in feel good TED talks, celebratory speeches, and the use of “vocation” as a way to get away with regularly ignoring basic workers rights.

This is a phenomenon that more and more designers are becoming aware of, and Lorusso argues for an idea of design that is rooted in the material reality that design is not an unstoppable, magical force, and we are not all doing perfect wonderful work that is totally disconnected from our actual lives. We are not carbon copy cutout 2010s hipsters, we are all our own people.

The project of local technology isn’t a sanitised design thinking excercise - it’s about actually connecting with communities, embracing the intersection of the creation of local technology and sociopolitical factors to create technology that can think of new ways of being in the digital age.

The repetition and banality of existing platforms is wearing thin, opening ground for technology rooted in actual life. Communities are exhausted with platforms that ignore their languages and histories, delivering content that doesn’t speak to them or their realities.

Local technology holds the key to changing this, but only if it exists in all communties. Right now, the access, knowledge, and ways of being that are needed to build local technology just aren’t accessible to everyone. Rethinking technology through the lens of community history and language use is an essential strategy for creating better and more effective local tech that moves from being a distraction to a tool that actually means something.

I've been advocating this and love this line of thinking, decentralizing tech into communities would have profoundly meaningful downstream positive effects for politics and the economy.

Great piece, lots in here about the intersection of tech and identity which I (and likely most people) would never consider. I'd definitely be interested to read more on this topic.