against the ai thinkpiece

on the ai slop discourse machine, the profit motive behind ai consciousness, and the limits of western understandings of intelligence

I can’t escape them.

I love to keep up with tech news. But, everywhere I look, it’s all about AI, how AI is eating our energy, our brains, and stealing our jobs, etc, etc.

To an extent, these reactions make sense. It’s no wonder we are all trying to process and understand this phenomenon in our own ways. But like most things in the digital age, this conversation is controlled by the various algorithms that run the internet. These algorithms motivate content that triggers our emotions - not content that is helpful. So, we end up with a thousand thinkpieces on AI, that all essentially say the same thing.

I have found this more irritating than I can possibly put into words. Which is why we are here today, because, if you have not already gathered, I am a being motivated mainly by spite.

The question I cannot escape is - are these thinkpieces actually creating anything productive? Or do they just make us feel like good little intellectual lefties, for consuming contemplating and regurgitating providing valuable insights on the latest discourse around the sorry state of AI technologies?

This exploration of the state of AI discourse is a follow-up to my previous essay on the collapse of online political education. The first installation in this series discussed how online political education as a project is slowly collapsing due to the limits of the project of educating people through the algorithm. This essay explores the specific example of AI Discourse in more depth, to demonstrate how these frameworks not only limit poltical action, but also shape the material limits of the conversations they produce.

money money money

The “AI Discourse Machine” is part of a wider system of emotion-driven, algorithmically controlled conversation that, at its core, primarily exists to harvest and sell data. AI itself does not make much money. By all measures, it is losing money. Its value lies in its cultural capital - how people think about it, how often they think about it, and their increasing reliance on it. This creates data, this data is sold, and this data makes money.

The Discourse Machine is a big money maker for all sorts of online pundits - and for tech leaders. They have to have social standing to make a splash. Much like in the miniseries “The Dropout”, characterising the rise and fall of the catastrophic company Theranos, led by Elizabeth Holmes, tech leaders like Sam Altman, Elon Musk, and Peter Thiel, rest just as much of their value in the discourse they generate. Because they have the same individualist notion of tech leaders as Elizabeth Holmes did, and they crave the spotlight - but also because this gives them data.

What do you think Elon Musk is doing with all the data generated every time he throws a hissy fit on X? Just letting it sit there?

We often lament about “data capitalism” - but we forget precisely where this data comes from, and how it is generated. Ultimately, this data is generated from our emotions and how we express them online. In the faux-rationality of the libertarian tech world, this is merely meant to allow people to make better products and make everyone happier.

But people aren’t rational, and profit incentives that lean towards invoking strong emotions are always going to lead to manufactured outrage. Just like we end up with AI slop about “what if Donald Trump was actually Shrek,” we also end up being fed 1000000 tidbits of algorithm-friendly “hot takes” on AI. This is why most of us, I imagine, are getting quite a bit sick of the constant thinkpieces thrown at us.

If you are on the left, you are often fed everything about how AI is terribly evil, and if you are on the right, the opposite. Neither of these narratives surfaces the nuance or complexity of the technology. We find ourselfs in leads to a situation where everyone, regardless of political opinion, is talking themselves and their peers in circles, trying to please the Mighty Algorithm (which uses AI technology, by the way).

is ai eating our energy?

One example of how this narrative can quickly spin out of control is the narrative of how AI uses so much energy, so you, for using AI, are a morally bad person and should be punished with 20 mean comments. All of which, no, are not also using energy to comment and driven by an algorithm that uses AI and therefore energy.

Why would you ask such a thing? I am merely a concerned citizen, and better than you, obviously.

Moral grandstanding aside, the notion that AI is a beast that consumes energy is slightly more complicated than it appears on the surface. Data centres, cryptocurrencies, and AI systems together accounted for roughly 2 percent of global electricity consumption in 2022, or around 460 terawatt-hours. Within that total, however, the proportion directly attributable the everyday, low-intensity kind of use like asking ChatGPT to check your spelling, is vanishingly small, coming to only about 0.02 percent of global energy consumption, according to European Central Bank estimates. Most of that energy concentrates in data centre operations and in resource-heavy model training rather than ordinary user interactions.

There are real harms emerging around where and how this infrastructure is built, but those harms are structural rather than moral. For instance, many new AI data centres are popping up in rural and economically vulnerable regions dependent on fossil-fuel power. In some US states, backup diesel generators used by these facilities have released hundreds of times more nitrogen oxides than typical natural gas plants, disproportionately impacting Black rural communities already suffering the highest mortality rates from air pollution.

So yes, there are victims in this system, but they result from an extractive corporate logic, not because someone ran a chatbot request. Let’s not plastic-straw this conversation into a question of individual virtue when the issue, as ever, is structural.

Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World captures this kind of moral confusion well. Her argument turns on how conspiracy culture thrives in algorithmic environments that reward outrage over reflection. Through the metaphor of the “mirror world,” she describes how digital systems refract anxieties, turning political and ethical complexities into caricatures of good and evil. When you attach morality to something like AI energy consumption—casting users as sinners or saints—you risk falling into the same outrage-driven circuits that conspiracy theorists find themselves in.

slop or not?

I came across this article in Wired that discusses the social media account “Neural Viz,” which you may have come across in your doomscroll adventures. It features these alien creatures in various forms, discussing everything from X to Y in a way that delightfully parodies our own society. In the interview in Wired, the creator of the account provides very interesting insights into how he integrates AI into his workflow, and what he thinks about it’s value.

Neural Viz isn’t what you think about when you think about “AI-generated content.” It’s not slop. It’s clever, interesting, and uses a unique form of storytelling to add more depth and value to the cultural conversations it touches on. It is, arguably, demonstrative of what the internet can be, how social media feeds, as an art form, can give way to interactive storytelling that is geniunely entertaining, informative, and unique. But this kind of AI content can be conveniently ignored when we are thinking about what AI is and what it means for society - instead, we focus on the cat videos, and the other type of content that is clearly damaging.

I posted a video to my Tiktok highlighting this contradiction in what we think AI content is, and what it really looks like. I got a number of colourful responses, but one that made step back and reflect on the nature of online conversation was “I would define this as creative because it could have been created before AI.”

But is that what creativity is? Are we really able to answer one of humanities most puzzling philisohpical questions in this way?

I don’t really have the answer to this question, but that is precisely the point. Maybe it is to do with some intrinsic human quality (although, as we will learn later, that is a notion that I would generally reject).

The internet discourse ecosystem pressures us to have quick answers - to have a “take,” because Big Tech ultimately profits from this. We don’t always need to have quick answers. I don’t know what exactly Neural Viz says about the future of AI technology - and I wouldn’t claim to. I don’t know a lot of things about AI, and how it exists in the world. That’s what the rest of this essay is about.

collective intelligence

Much criticism of AI is rooted in the idea that it is somehow “lesser” than human intelligence. This may seem intuitive, but the reality of what intelligence is and how it comes about is far more complex than this. A hatred for “machine intelligence” necessitates putting human intelligence as supreme, an ideology which is far darker than it appears on the surface. It also necessitates understanding and defining what human “intelligence” is, which is an equally complex task.

This extends into the conversation on the online left quite significantly, with an all too present AI hatred that is almost equally as religious in nature as the pro-AI ideology espoused by Altman and Thiel. This narrative takes the assumption that human intelligence is supreme as a given, using this to dog on AI and people who use it.

what is consciousness?

The hard problem of consciousness is a pet interest of mine, and has been since I was about 17. It describes the philosophical challenge of explaining why and how physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experience — the inner sense of “what it feels like” to be conscious. While we can understand the operations of the brain, we cannot explain why those operations produce a sense of “what it feels like to be me.” The debates around this have given rise to a number of different theories on what intelligence, or consciousness, is, and how it forms, including but not limited to:

Physicalism (Materialism): Consciousness emerges from complex physical or informational properties in the brain, and thus can be replicated with careful computing (probably).

Dualism: Consciousness is fundamental and non-physical, separate from physical processes. This is a typical religious view of “a soul” existing, and therefore, machines cannot possess consciousness or intelligence in the human sense.

Panpsychism: Consciousness is fundamental and universal, existing in some form in all matter.

These perspectives can shed light on the problem of assuming human intelligence is superior to machine intelligence. It’s not taken as a fact, and a number of these perspectives have pretty problematic ideologies behind them. The insistence that consciousness is something that happens inside a person, inaccessible and self-contained, mirrors the capitalist myth of the autonomous subject. Thought has always been produced socially, within our different social systems, hierarchies, and the labour that fuels them.

a centrist perspective

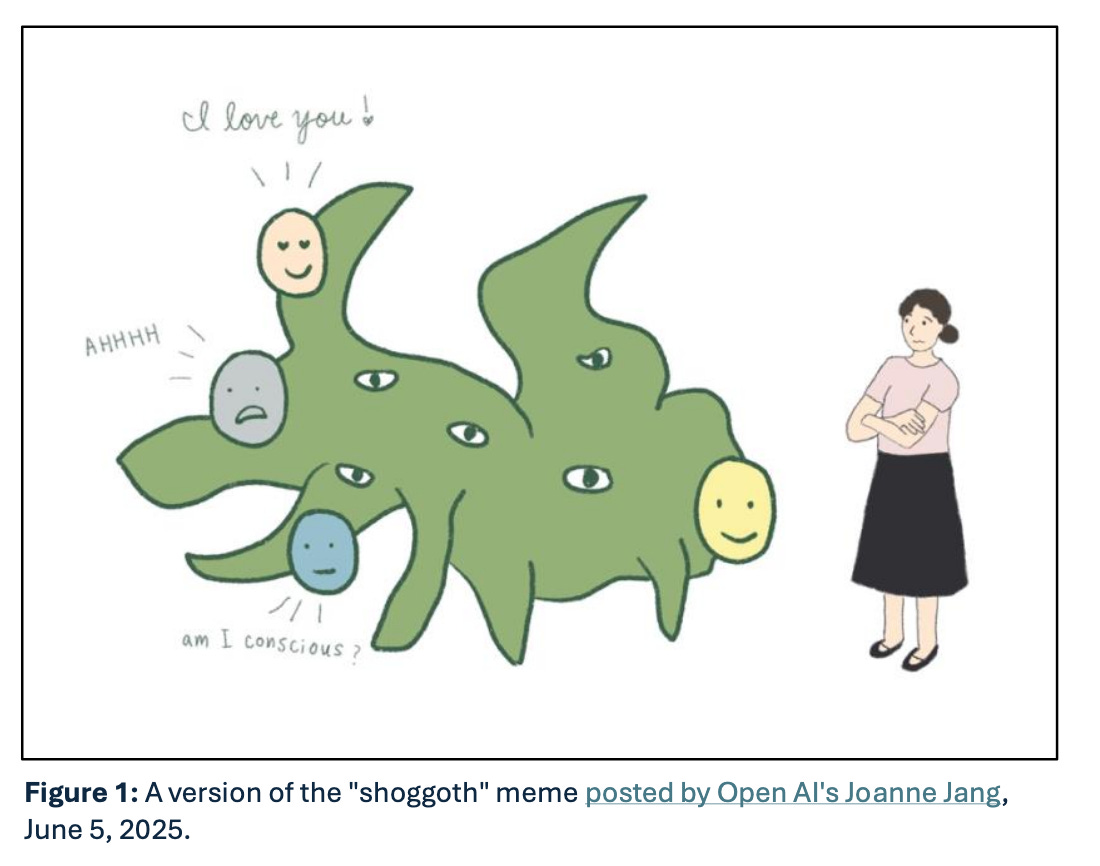

Jonathon Birch’s “AI Centrist Manifesto” describes a perspective on AI consciousness that rejects both extremes - the notion of digital souls and the notion of human supremacy. Millions of people are already misattributing humanlike consciousness to language models, mistaking mimicry and memory for consciousness. This inherently disproves, or so he argues, the behaviourist notion that consciousness can only be determined through observing external behaviour.

Birch instead proposes that nonhuman consciousness would not resemble our interior life. It might not involve feelings or selfhood at all. It could be distributed, data-driven, and alien-like.

I found this theory deeply intriguing as it presents these issues in terms of the design challenges they present. How would you successfully demonstrate, through means of the visual interface, what “kind” of consciousness (or lack thereof), AI systems possess? What are the very real dangers of the misattribution of consciousness, and what can we do about them?

the profit motive of conciousness

To me, the most intriguing part of Birch’s theory is the implicit question that is never stated out loud.

AI companies directly benefit from the misattribution of consciousness, since it creates a disconnect between them and the harmful impacts of their products. Around 39% of people trust AI chatbots - but only 15% trust AI companies. The harm then appears abstract, detached from the people who built and deployed them.

The state of the AI industry today creates an environment where particular perspectives on intelligence and consciousness are privileged. They are profit-motivated to make you think their AI is conscious, and to do that, they need to build a consensus for this idea. The current political and economic system (capitalism, if you’re not keeping up) cannot be used as a framework through which to understand what machine intelligence is. It is not capable of doing so, as it will always inherently bias the perspectives that make more money.

oh look, it’s colonialism (again)

None of this, however, really holds the answers. These theories, as compelling as they are, are just as shaped by colonialism and white supremacy as the notion of human intelligence is in the first place.

A couple of weeks ago, one of the authors of “Making Kin with the Machines” reached out to me to suggest the paper as a perspective on AI that might interest me. Despite all my travels in the world of different theories of AI consciousness and intelligence, I had never come across this work in any meaningful way.

Drawing from Cree, Lakota, and Hawaiian epistemologies, the writers describe how intelligence is already relational, already shared. To “make kin” with machines is not to humanise them, but to recognise them as participants in a network of obligation and reciprocity. Against the colonial logic of extraction or ownership, this framework asks how we build technologies capable of belonging — not as tools, but as relations.

Theorists like Birch announce their work as radical, as if they’d uncovered something entirely new by daring to think of minds collectively, or thinking beyond the human. The people who claim to be mapping new terrain for ideas like relation, collectivity, or nonhuman consciousness are standing on ground already charted — just renamed, stripped clean of its origins, and dressed up as innovation, which is part of a wider pattern of how the West presents “innovation.” The Left's refusal to engage with ideas about what machine intelligence is beyond hatred of AI also ignores these perspectives, playing into the very colonial ideas of human intelligence and superiority that have undermined these Indigenous perspectives for centuries.

As I discussed in the last instalment of this series, the nature of algorithmically motivated online political education does not inspire action. It can also limit our learning. These two perspectives are deeply tied to one another, where these simplistic emotion-driven narratives about AI create a mimic of our emotions that drives the data economy; they also narrow our possibilities, introducing us to the ideas of machine intelligence from a place of artificially manufactured fear.

There are also a LOT of really interesting works going on in the UX of AI/the UX of Automation, which I have geninely really enjoyed keeping up with. This is not quippy thinkpieces, but the deeply nerdy interaction ideas that keep me up at night. If that’s more your bag, I’d reccomend checking out the Sendfull substack.

If I was to accept the “AI Slop will kill us all,” narrative, not only would I have not discovered the real reason AI companies want you to think their chatbots are conscious (capitalism, yay,) I also would have been participating in a colonial system of silencing that the very same internet know-it-all lefties I discussed in the last instalment of this series are guilty of.

I think a lot of the discourse on consciousness - in this issue - is misplaced and just confuses things. Intelligence could be defined in a limited way so as to be applied to machines, but only so far as they replicate whatever we understand the human faculty of intelligence to be. I think where a lot of the heated reactions come from is the idea that human=consciousness=intelligence. That's not surprising in the circumstances. I think a way out of that kind of heat is to take the most important distinction to be what is natural and what is synthetic, or even better (with less unsavoury ideological associations) between 'phusis' and 'techne'.

Great piece! Yes, definitely a marketing myth. The myth of Artificial Intelligence by Erik Larson deconstructs this myth. I'd add there's another big myth. Not of AGI or Consciousness, but of utility. OpenAIs return on Investment hinges primarily on getting people (and orgs) to believe that they cannot compete without AI. Once we are dependent, we'd be willing to pay anything.